Once upon a time (~1865 to ~1949) there was a land, the United States of America, which possessed existential security from external threats. Parked between two oceans, America had good reason to consider itself safe. Foreign nations could certainly attempt a reverse D-Day on America’s shores and push their way into the heartland, but the odds were stacked against such an attack. America was a defensively hardened target.

The stopping power of water worked both ways - oceans made attacking America hard, but also made it hard for America to attack other places. To an extent, the US and the rest of the world had mutual security, mediated by oceans.

Then came technologies of nuclear deliverance. At first, it was just the United States that got the bomb. Getting it first, the US remained existentially secure, but possessing atomic weaponry made other nations existentially insecure.

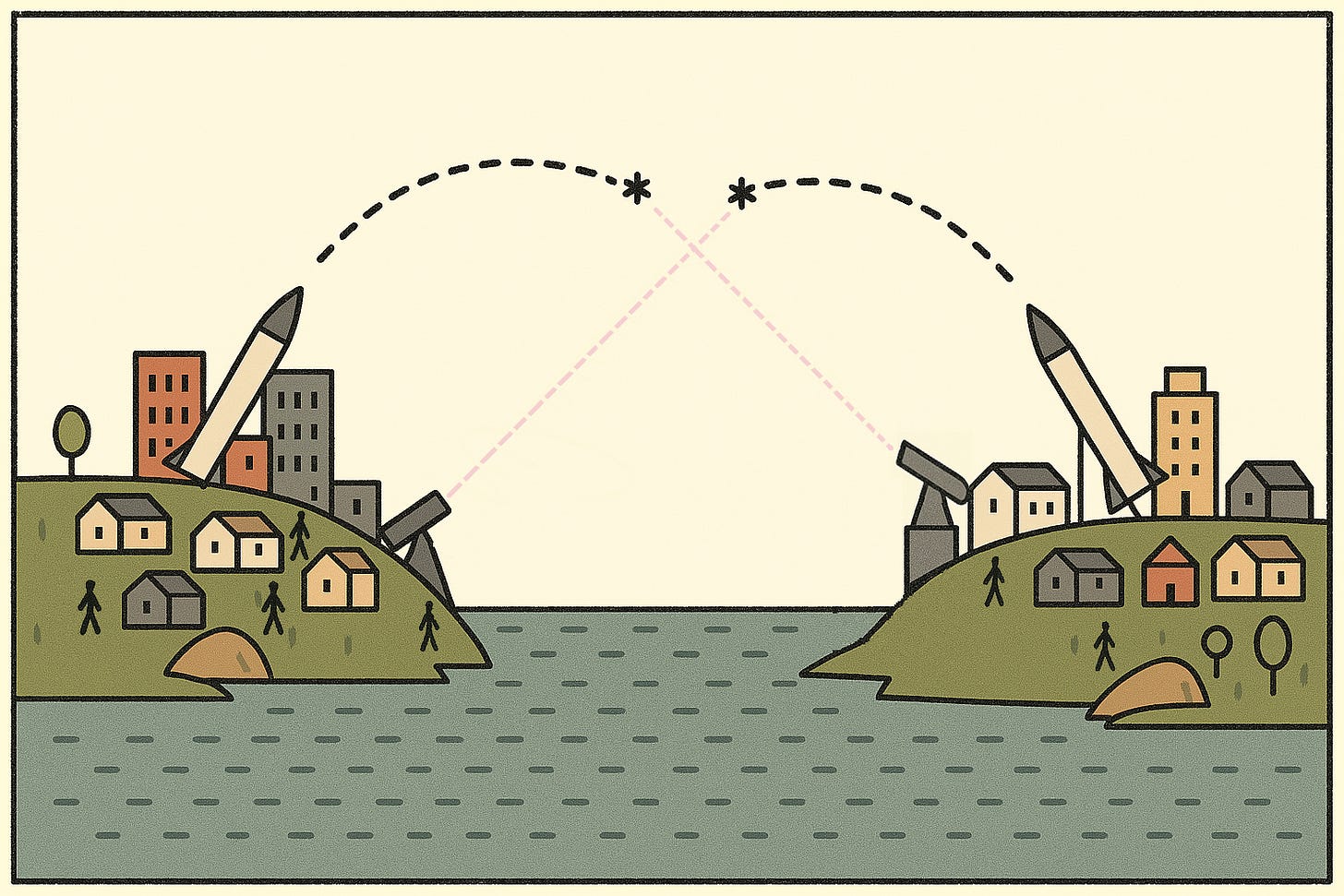

This asymmetry in strategic assets would be temporary. Any other nation could develop their own nuclear warheads and intercontinental missiles, which together would give them the ability to strike anywhere in the United States. Russia got the bomb in 1949. More nations followed. The United States of America became existentially insecure. Forget about a reverse D-Day, which would require other nations conquer America bit by bit starting from the country’s territorial edges - in the atomic age, an enemy attack could begin in Chicago or Kansas just as much as New York or San Francisco.

This period was perilous! Some cold warriors knew the US had a strategic advantage and wanted to use it before other nations had parity. Atomic weapons were fast enough to deploy that a first mover might be able to knock out their opponent before they could get the chance to respond. There were multiple close calls over years of uncertainty and anxiety.

The world was early in a new international strategic regime: mutual insecurity.

As it happens, the nobody used their strategic assets to pre-emptively stop others obtaining their own. Other nations built up their own arsenals. Close calls fatefully de-escalated. New developments, like submarine-launched nuclear weapons, reduced the need to fire fast in the event of a crisis. Early mutual insecurity, which was unstable, progressed to late mutual insecurity - the international security regime which we live in now.

Mutual insecurity is terrifying. “Nuclear deterrence is supposed to feel awful”. It is existential fear that disciplines nations into mutual non-use of strategic assets.

Terror and fear are not nice feelings to feel. America sought ways out of this condition. Ronald Reagan pursued missile defence technology in the 1980s (the Star Wars program) with the notion that perhaps the US could return to the good old days of existential security if it could shoot down nuclear missiles.

As it happens, missile defence systems are imperfect. They can’t catch every missile, and this means other nations can counter them by increasing the volume of potential attacks.

But this may not hold forever. Eventually there may come a time when comprehensive defence against intercontinental nuclear-tipped missiles will be possible.

If anyone really were on the verge of successfully exiting mutual insecurity by building comprehensive defences, then other nations would have to decide, before the window of opportunity closes: use it or lose it.

To “use it” would be an apocalyptic decision. A “bloody nose” with non-nuclear missiles, aimed just at the sites where defence systems were being built, would be hard to differentiate from a nuclear attack. Even if properly communicated, such an attack would begin an escalatory cycle that could end in full war.

It might be better if nobody seriously pursued comprehensive defences. But if anybody does attempt an exit from mutual insecurity, it would be better if everyone else decided not to “use it”.

If other nations “lose it”, this would be good for the world. It would also be good-will and good precedent: Nations don’t interfere with each others’ comprehensive defence plans.

A window of unidirectional insecurity could then be followed by a return to mutual security, this time mediated by technology.

Could this cycle repeat again? Certainly it could. New offensive technologies might be discovered, conferring a strategic advantage to the first nation to build them. The security regime could be upended again, like it had before.

We’ve played this iterated game once so far. We might soon play this game again.

If we want to survive every future transition, we should create a good track record.

This post was inspired by The Course of Empire paintings and also the comic and meme Our Blessed Homeland. Images made with ChatGPT and lightly edited.