Matthew Yglesias came out the other day against debate. I disagree. So: One two three four I declare a word war.

Matt’s central points are:

Debate isn’t persuasive.

Debate is not truth-seeking.

These issues arise mainly in verbal debates. Written debates, for example, are better.

Aggro tactics don’t work.

My positions are:

Debate is persuasive, actually.

Debate promotes truth, actually.

Verbal debates have some significant advantages compared to written debates.

Agreed, aggro tactics don’t work, but aggro tactics are bad debating.

Debate is Persuasive

Do audiences who watch debates change their minds?

Matt says no.

In Matt’s personal experience, debate has never been persuasive.1 He says this lack of persuasion from debate is because “the very act of debating pushes people into soldier mode” and that going in “guns blazing” “is not how persuasion works”.2

Empirically, however, Matt is wrong. Debate is persuasive.

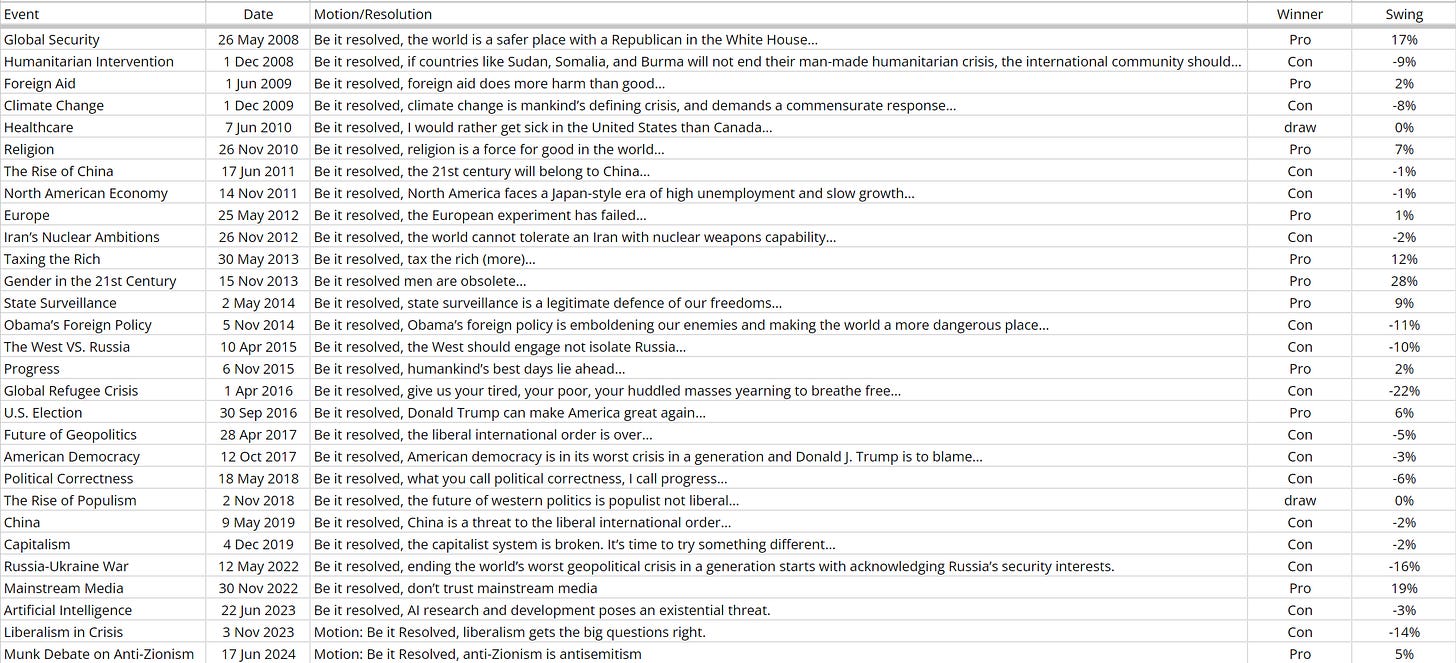

For example, Munk Debates polls its audiences before and after each televised debate that it hosts. The results are posted online along with the videos. Here’s a summary of audience swings before and after:

On average, 7.7% of the audience changes their stance on the issue by the end of the debate. Taken literally, that’s incredible levels of persuasion! Name another 1-2 hour intervention as effective at altering opinions on controversies as stark as whether religion is good (7% swing), men are obsolete (28% swing), Donald Trump can make America great again (6% swing), or anti-Zionism is antisemitism (6% swing).

But Munk Debates’ data is a bit thin. Luckily, another public debate organization, Intelligence Squared, polls its audiences both for and against, as well as whether they were undecided. I’ve hand-compiled the data over here, along with the Munk data.

The undecideds make up a large minority of most audiences. Using data from 66 debates from 2004 to 2022 (everything I could find where data was provided in the publicly available video clips from Intelligence Squared), on average, 28.1% of the audience in a given debate is undecided at the start. This number consistently declines, with an average of 5.3% of audience members still undecided by the end of the average debate.

Evidently, people are learning a lot and forming opinions from debates!

How do we square the popular experience of debates with Matt’s personal experience? Matt writes that when he participated in a debate, he didn’t find the opponents convincing. Moreover, when he listens Mehdi Hasan debate as an audience member, again he doesn’t find himself persuaded.

As it happens, I too find debates rarely alter my opinions. I’ve been a professional debate coach for a decade and consumed an above average share of debates, amounting to thousands of rounds. Debates very regularly update how I think about persuasion and good argument. But on the subject matter itself, if I had to ballpark it, I’d probably say the hit rate for me changing my opinion because of the arguments presented in a debate is something like once every 50-150 debates. It’s pretty rare! Notably, not zero, and I’d say my hit rate for intellectual consumption in general (seminars, essays) is also not that high – but still, why aren’t Matt and I having regular belief changes from debates?

This experience Matt and I share with debates is entirely explicable – Matt and I have already formed opinions on a wide range of topics! Only a a minority of people – 28.1% – enter debates without a formed view. The rest of us, including Matt and I, walk into debates having taken a side already – naturally we find debates don’t change our view so much.

In the case of Matt’s personal debating experience where his opponents beat him, it’s extra clear why he wasn’t persuaded – the opponents in a debate are not the target of persuasion. The target of persuasion is the audience. Matt’s opponents weren’t trying to (nor needed to) persuade him, they merely needed him as a live prop against which arguments could be juxtaposed to persuade the audience. The last people in a debate that are expected to change their minds are the debaters themselves – they’re not there to persuade each other!

One objection to the data presented could be: Is this proving that people are changing their view from one side to the other, or is this data just showing that debate tends to politically activate people who were otherwise apolitical? If the latter, maybe this evidence from debates is actually bad news! Perhaps it means that debates don’t persuade in the sense of changing minds across the aisle, but instead represent an accelerant to polarization.

I think people forming views on questions is good, not bad – I would love more people to learn their opinions on questions. An opinionated citizenry, informed by arguments, having had the chance to hear both sides, is good, even if we don’t reach consensus after only one dialogue. But let’s grant that it would be bad if all debate did was shrink undecideds to drive up committeds. Is that what debate is doing?

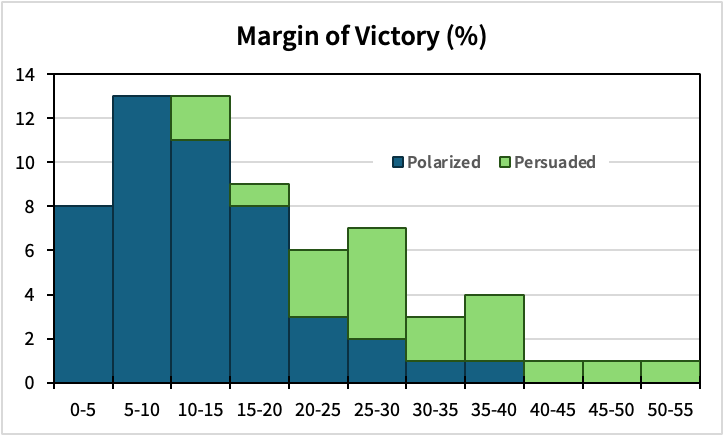

One way we can investigate this question is by looking at how often debates result not only in a reduction in the number of undecideds, but also result in a reduction in the number of supporters for one of the two sides. We can go into the Intelligence Squared debate results and find that sometimes a debate will increase the share of the audience supporting both sides (by decreasing undecideds), which we can classify as polarization outcomes, and sometimes a debate results in one side losing votes to the other (regardless of what the undecideds do), which we can classify as persuasion outcomes. If we do this, we find that 28.8% of the time in twenty years of televised public Intelligence Squared debates, audiences actually shift from one side to the other – that is, genuine mind-changing persuasion! Most of the time (71.2%), the undecideds become decided, and both sides of the debate gain adherence – though of course, in many cases, quite unevenly, clearly favouring one side rendering a clear winner.

I’d say an intervention that unambiguously changes minds more than a quarter of the time is pretty persuasive! We also don’t have figures for switching that cancelled out, so the number of changed minds is probably larger.

Public verbal debates are persuasive. As it happens, Matt is at odds with one of the traditional critiques of debate, which is premised on debate’s persuasiveness. The critic says: Debate is persuasive, that’s the problem, because a good debater can convince people of an incorrect position.

On this point, Matt agrees – he thinks debate is tenuously connected to truth.

So, is debate promoting truth?

Debate Promotes Truth

I think claims of whether debate promotes truth are often made with a lack of comparison to alternatives, especially alternatives that are comparable to debate in the relevant ways.

Here is what debate is: Debate is a procedural rationality. As a procedural rationality, debate is generally used for controversies – that is, a question which is not super obvious. Debate is also a form of dialogue. It’s people talking.

In-order to say that debate is bad for truth, one has to show that debate is contributing something uniquely that alternatives are not doing. All dialogues can have bad-faith participants. All audiences have cognitive biases. Controversies – being controversial – tend to animate people emotionally over fundamental value differences or invite motivated reasoning due to personal stakes in the question.

You can certainly say, well let’s just not bother with controversies – but controversies are important to deal with! You can also say well let’s not do a dialogue, let’s do some totally different thing, like laboratory science – and that’s fine but lab science isn’t a form of dialogue. They cost way more time and effort and are inaccessible to most people, and it’s reasonable to say we need a procedural rationality for discussion at-scale and with the evidence we already have. You can also say that debate is not the best type of dialogue to rationally interrogate a controversy at scale – and this I challenge you to do, because debate is one of the best options, and I’ll now argue why.

As a procedural rationality, competitive high school debate and public verbal debates have several really valuable features that make them excellent at moving participants towards truth.

First, both public verbal debates and competitive debating have win conditions (e.g. before and after polls of the audience). This is super valuable! It means that debaters are given meaningful feedback on whether or not they are in-fact being persuasive. Strong debaters learn to focus on the best arguments for their side, and learn to not bother raising irrelevant material. Mehdi Hasan, being a strong debater, cleverly prioritizes the most convincing examples for the audience he intends to persuade: He’s a progressive arguing for progressive positions, but he does so, for example, by defending the constitution or highlighting crimes perpetrated against police officers. Mehdi specifically seeks out premises that his intended audience agrees with to meet them where they are at and persuade them that on their existing beliefs, they should agree with Mehdi. Debate was the training that made Mehdi so good at this!

Second, public verbal debates and competitive debating create a natural check against bad arguments by placing two people motivated to identify flaws in the other side in immediate conversation, with equitable time to critique each other. This is awesome! It solves two issues that are quite common in non-adversarial dialogues or written debates. One problem is that audiences may not even notice when a major flaw in reasoning or false but seemingly convincing point has been made. Having a motivated party who can critique major errors is super useful for an audience that isn’t immediately familiar with the topic or really keeping tight score as the points are being delivered. Another problem, which comes up in non-adversarial dialogues but even comes up as well in written debating, is that participants often can get away with never addressing a key opposing point or pesky fact. A live debate, where participants can directly challenge each other, can place extremely rare pressure on someone who would otherwise avoid talking about something – and this is good! People shouldn’t dodge important points. The audience deserves to hear a response. And if your position is solid, then you should be able to respond!

Third, public verbal debate and competitive debate have rules and moderators. A good moderator keeps the conversation on-topic, can fact-check an egregiously false point, and prevent participants from yelling over each other. Speaking times and interruption rules also help. Recall that mics were turned off between the presidential debates in 2020 and 2024 to try and prevent yelling over each other – something you can just do if you’re running a debate!

Fourth, public verbal debates are the most practical way to engage large numbers of people in politically and intellectually important questions. Mehdi Hasan’s Jubilee debate video has racked up nearly ten million views. Some of Intelligence Squared’s debates have been watched by millions of people, for example debates on the Catholic Church or anti-Zionism. The US presidential debates, of course, are a huge spectacle, watched in 2024 by as many as 67 million people.

So what’s the next best alternative? Matt suggests written debates:

Much better than verbal debates are written exchanges of views.

I doubt that this Democracy Journal exchange that I did with Elizabeth Pancotti and Todd Tucker is going to fundamentally alter anyone’s view of the situation, but I do think that it at least clarifies the issues. ...

This kind of dialogue is valuable largely because it helps distinguish between points that the people on one side like to raise and the actual issue at stake.

Written debates are great! I wouldn’t say you should never do them. However, Matt’s example illustrates their key weakness: They’re boring and low engagement. I’m sure Matt got more out of the written exchange intellectually with Elizabeth Pancotti and Todd Tucker than he has with public verbal debates, but I had never heard of this written exchange before. By contrast I happened on the Jubilee debate even before reading Matt’s article. The Jubilee debate has ten million views, and I can only assume the Democracy Journal exchange is working with pretty small numbers. Just having a conversation, a verbal back-and-forth, no audience at all, is also pretty rewarding intellectually, including with someone you disagree with. It’s okay to do low-engagement dialogues!

But if you want to achieve volume on intellectually important questions? Do a public verbal debate. As a public intellectual interested in persuading people, Matt should really consider doing public verbal debates. He’d give himself the opportunity to move way more minds that way.

Another downside with written exchanges is the audience usually consumes only half of the content. Maybe someone reads Matt’s initial point, or someone’s response, but the full back-and-forth, as a media product, is split across multiple platforms and places. Debates puts the whole back-and-forth in one spot, saving the audience inconvenience and enriching them with points and counterpoints in full view.

There are also other minor things that verbal debates have over written debates. Time limits discipline the speakers to focus on core material – writing has no limit, and so essays can get overlong. Written debates take 1-2 thousand words of text before the next person responds, whereas debates keep contrast high by having the participants speak right after one another, often with a section for a free-flowing back-and-forth. Verbal debates create stakes, encouraging the participants to prepare thoroughly.

One further concern often raised that Matt raises as well is that debate is a skill that is specifically truth-agnostic.

Still, consider Joe Biden shitting the bed in his showdown with Donald Trump. That was an informative evening in American politics, but it didn’t inform us at all about the policy issues being debated. Biden’s inability to think on his feet under pressure or give cogent responses was a big deal, but it didn’t change the fact that the stuff Trump was saying about tariffs and about taxes and the budget deficit wasn’t true. Democrats brought in a new nominee who didn’t differentiate herself from Biden much on the substance of policy. When she debated Trump, she beat him handily, even though they were arguing about the exact same things. Then Tim Walz debated JD Vance, and Vance got the better of him, though by a narrower margin than either of the two presidential debates.

These were all arguments about the same things that just reflected differences in debating skills Harris > Vance > Trump > Walz > Biden — not anything about the underlying merits of the issues. As it happens, the candidate I voted for is the candidate who was best at debating. But the policies she was defending were basically the same as the policies of the worst debater in the group. Debate is just a skill that has a fundamentally tenuous relationship to ideas like “actually being correct” or “seeking out the truth.”

Matt is making the wrong argument here. In order to prove that debate is truth-agnostic he needs to show that skilled debaters can consistently convince people of false views, not just that true views are defended by both good and bad debaters.

My view is that having the truth on your side tends to give debaters a small boost. I don’t have stats for this one, but my intuition across thousands of debates is that there’s a not-enormous-but-not-zero benefit to being on the true side of a question. Debaters who contradict themselves look worse, and contradicting yourself correlates with being false. If you’re defending the wrong side, you’re more likely to run into contradictions. Debaters who say flatly false things lose credibility, have a harder time winning. True positions aren’t composed of false things, so the true side loses credibility less often. That means skilled debaters can convince people of false things, but there’s an asymmetry. It’s a harder for them.

Over enough rounds of debate, noise turns into signal, and debate as a practice points in the correct direction.

I also think that Matt maybe underrates benefits of debate that don’t specifically come from learning about the issues themselves. There’s value in understanding the psychology of people who disagree with you. There’s value in understanding how two worldviews are incompatible. I have found the experience of watching and doing debates extremely valuable for my own understanding of persuasion and how it works. What objections to people have to my views that they want to hear responded to? What bad arguments from the other side do people often raise? Debates offer rich feedback for debaters.

Presidential debates are also valuable on this level, offering opportunities for voters to learn personal attributes about the candidates. How do they handle pressure? Are they a skilled communicator? These are important parts of the job. Debate, as a dialogue type, applies pressure and creates a situation where communication skill is immediately one-to-one comparable. Valuable politically-relevant information is surfaced by presidential debates.

So does debate promote truth?

For controversies, it’s one of the best dialogue types to use if you want to procedurally discover truth on big questions and obtain a large audience. These situations are inherently really bad for truth. Controversies are often extremely emotionally charged because they cut at core value differences (e.g. abortion, capital punishment), and people often have very strong personal motivations to tilt them in one direction or another irrespective of truth (e.g. debates about taxes, economic policy). When debates are held on non-controversies, the only people who are willing to defend the other side of the question are often unreasonable (e.g. flat earth debates). You want a procedural rationality that is robust to all the problems inherent in controversies, dialogues, and large audiences - debate does the job.

My challenge would be: What’s an alternative type of dialogue that engages as many people and possesses superior mechanisms for procedurally achieving rational outcomes on controversial questions?

Aggro Tactics

Matt makes one additional point against debate that warrants addressing: That debating is aggro tactics and aggro tactics are bad.

To prove this point, Matt says he was slammed recently on Twitter when he raised on retweeted a right-wing organization making a left-wing point, both left and right having reasons to be upset. Matt remarks that trying to “win an argument” isn’t going to persuade people, but new information from “sources who are already trusted on a values level” is “how persuasion works.”

There are two problems with this argument:

First, Twitter isn’t a public verbal debate nor competitive debate, so using the behaviour of people on Twitter as exemplary of debate is mistaken. In many ways, it the anti-debate dialogue type – no rules, no moderator, no win condition, no set topic, no set speaking time – it’s not even verbal! It’s written!

Second, aggro tactics are not good debating – aggro tactics are actually bad debating.

Mehdi Hasan, whom Matt and I agree is an archetypal good debater, does exactly the sort of audience-specific argument-highlighting strategy that Matt endorses. Mehdi quite regularly references organizations and people who are politically opposed to him (“trusted on a values level” by those he wants to persuade) saying something Mehdi agrees with, with the emphasis of “even these guys admit my point!”

I think the problem Matt should have with people doing aggro tactics on Twitter is not that they are doing too much public verbal debate, but that they are doing too little! Debates where there are objective winners and losers discipline the debaters into being better, and they punish people who think their opponents are so obviously wrong that they don’t warrant preparing against. Being aggressive with your audience does not persuade them, and it’s a lesson your learn from public verbal debates.

Doubt

There’s more to persuasion than debate. Fiction is persuasive. Being empathetic and listening is persuasive. Building a relationship of trust creates conditions for persuasion. Debating can be persuasive – people do change their mind, and do learn things.

One of the ways I’ve personally experienced persuasion through debate is through doubt. Many times when you listen to a debate, you’ve already chosen your side. You hear points raised by the opponents to your worldview, and you think: They must be wrong, how would I respond to that point?

A lot of the time, when someone with a committed view hears a good point from the other side, they instinctively reject it. But the point is good. It’s a point that, at the very least, one should have a response to.

Mostly, these good points change nothing. But sometimes a good point sticks around in your mind – it forms a doubt. You maybe bring up this point in conversation with friends, see what they think of it. You try and come up with rebuttals. You do some additional reading on the point.

This process of doubting and reasoning and reflecting eventually terminates in one of two outcomes. One outcome is you change your mind, after a gradual process of realizing that this good point means that, ya, they were right about what they were arguing for. Or, you preserve your existing worldview, but enrich it, because now it is built to withstand a good point by the other side. You come to believe your beliefs for better reasons.

It’s really hard to measure this part of how debate causes persuasion – how many years does it take? But I’ve experienced it many times myself. And it’s because of debaters and debating. I think that’s good, and I think we should keep doing it.

Matt: “... it strikes me that I’ve rarely found myself persuaded by a clip of Hasan, or anyone else, outdebating someone. ... One of the rare times I participated in a formal debate was an Intelligence Squared debate, where a self-publishing success story and I went up against Frank Foer and a traditional writer on the question of whether the rise of Amazon was good for readers. We got our asses kicked, but absolutely nothing about the experience gave me a moment’s pause about the actual issue.”

Matt: “If you actually want to get someone to change their minds about something, it’s not constructive to show up, guns blazing, with a plan to “win the argument” and demolish their worldview. People understand that the point of a debate is to win and that someone who is debating them is their enemy. The very act of debating pushes people into Soldier Mode where they’re trying to defend their position, and out of Scout Mode where they’re trying to learn about the landscape.”

I think that there's a big part of persuasiveness in debate which is totally disconnected from truth - i.e. rhetoric, appearance, knowledge of the form, etc. - and that part is more significant in debate than other mediums (such as the written alternative). I've felt this myself - I recall a debate round I watched where there was a speaker with incredible rhetoric and turning to someone at the end and saying "They must have won", and them saying, "They didn't actually say anything of substance" (which was true).

I think it's a real downside to debate that no matter how vigilant I am, the skill of debaters is going to influence how I perceive the substance of what they say. I ultimately think the medium is still valuable for a lot of the reasons you outlined (more engaging + forces contentious questions to be addressed), but the skill piece is unfortunate.